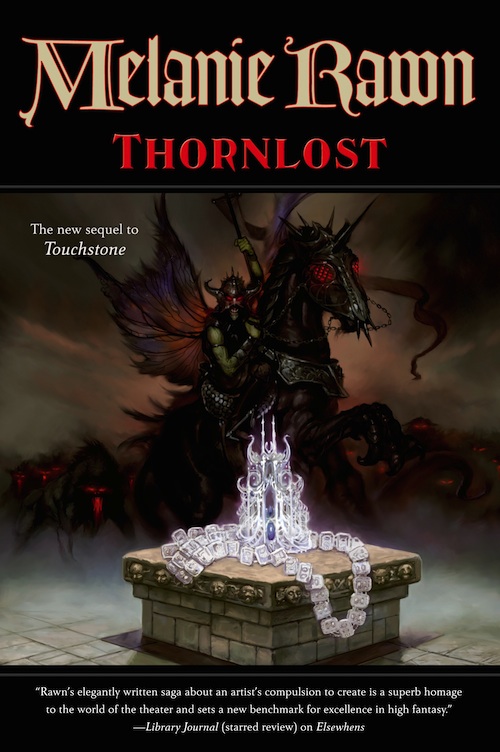

Melanie Rawn returns to her rich high fantasy world in Thornlost, the third novel in the Glass Thorns series, available April 29th from Tor Books!

Cayden is part Elf, part Fae, part human Wizard—and all rebel. His aristocratic mother would have him follow his father to the Royal Court, to make a high-society living off the scraps of kings. But Cade lives and breathes for the theater, and he’s good, very good. He’s a tregetour—a wizard who is both playwright and magicwielder.

It is Cade’s power that creates the magic, but a tregetour is useless without a glisker—an elf who can spin out the magic onto the stage, to enchant the audience. And Cade’s glisker, Mieka, is something special too. So is their fettler, Rafe, who controls the magic and keeps them and the audience safe. And their masker, Jeska, who speaks all the lines, is every young girl’s dream.

They are reaching for the highest reaches of society and power, but not the way Cade’s mother thinks they should. They’ll change their world, or die trying.

Chapter 1

Reality intruded on Cayden’s notice in the form of a flaming pig. Seated in a place of honor in the small courtyard of Number 39, Hilldrop Crescent, he had an excellent view of every marvel of cookery that came out of Mieka Windthistle’s kitchen door. Each was placed on a long trestle table for inspection by the guests, many of whom Cade didn’t know. Friends and family were in attendance, of course, but there were also neighbors who knew the new residents of Number 39; those who didn’t yet know them but were untroubled by the scandalous reputations of theater folk; those who were curious; and those who simply had heard that food and drink were to be had all afternoon and into the evening. Fortunately, Hilldrop wasn’t a large village—a central cluster of shops and two small taverns, mayhap forty houses, most with a bit of acreage for grazing, and a tiny Chapel visited every fortnight or so by a Good Brother or Good Sister attending to the spiritual needs of the village. Simple folk they were in Hilldrop, all Human to look at, though with a hint of other races here and there, and Cade had found them friendly enough. They’d no reason not to be. There was music all afternoon, local musicians on flutes and drums thrilled beyond words to be accompanying the famous cousins Alaen and Briuly Blackpath and their lutes. Later there would be dancing round the bonfire. For now there was a parade of culinary wonders, all presented first to Cayden Silversun.

There was also thorn, but that was not offered to other guests. Cade had been doing quite nicely all afternoon on a combination of very fine ale and one or another of Brishen Staindrop’s mysterious concoctions of thorn. The latter was responsible for the way he saw the food. First had been a completely feathered purple swan that blinked its glassy green eyes, stretched its wings, and flew off its platter into the lazy spring afternoon. A little while later a blue and red striped lamprey—fully five feet long and glowing like a lantern lit by Wizardfire, coiled in a bed of salad greens—was sliced its entire length by a sharpened snake wielded by Mistress Mirdley. It spewed dozens of tiny yellow butterflies that followed the swan skywards. A pink porpoise was next, arched above frothing cabbage waves that shimmered white and green in the gathering dusk. The poor thing flapped its orange fins in valiant effort, but failed to join the butterflies and the swan.

Some part of Cade knew that none of these things actually happened, and that the swan, lamprey, and porpoise had all been the proper colors and carved up and eaten. Plates had been given to him, loaded with meat and appropriate garnishments. But it suited him to choose to believe in the butterflies.

The pig was different. As the sun dipped below the western hills and vague spring shadows spread through the courtyard, all the lovely prancing colors and blossoming visions dissolved when the pig was brought out on a pair of planks, ablaze from the curl in its tail to the apple in its mouth. He expected it to do something: snort rainbows out its snout, leap upright and dance a jig. (A piggy-jiggy, he told himself, vastly pleased with the rhyme; he’d make of himself a famous poet yet, see if he didn’t.) At the very least, the flames ought to turn to glass and, fittingly for Touchstone, shatter.

But the flames were real, and as the rumbullion burned out, the pig did nothing more spectacular than lie there on the planks. Space was made on the table so Mistress Mirdley could carve with a knife that was definitely a knife. As a plate was piled for him, Cade’s last hope was that the apple would sprout wings and flutter off to join the butterflies. The apple stayed an apple as the plate was presented to him: his Namingday, after all, and his the honor of the prime slices and garnishments. He smiled past his disappointment that the thorn had faded, and made much of praising the pig that had betrayed him by staying a pig.

With the thought of betrayal, he absolutely avoided looking at Mieka.

Mieka’s mother-in-law, who had betrayed Cayden’s secret to the Archduke after Mieka had drunkenly burbled it to her daughter, had been sneaking sidelong looks at him since his arrival. He could guess what she was thinking: There must be some sort of mark on him, some significance of face or glance that indicated he was something other than a Master Tregetour newly turned twenty-one years old. That which he truly was, some sign must needs betray.

That word again. With his extensive—nay, exceptional—vocabulary, he ought to be able to think up something else to call it. But a betrayal was a betrayal, just as the pig was a pig, and when Mieka came by to refill his glass, the last lingering bit of thorn mocked him by overlaying the glisker’s perfect, quirky Elfen face with a snuffling swinish snout.

He realized he was writing it all in his head, and quite badly, too. For one thing, he was punning—snout was local colloquial for someone who betrayed his mates to the constables—and Cayden never punned. Worse, as if that triple s of snuffling and so forth weren’t bad enough, the odd little almost-rhyme of local colloquial was just plain awful. He was a Master Tregetour. Before inflicting things like that on anyone, including himself, he ought to rip his own brains out through his nose with a hoof-pick.

It was definitely time to go home. He’d been here since the afternoon, partaking of liquor in public and Mieka’s collection of thorn in private. It had been over two hours since the last pricking of mysterious powder, and Mieka hadn’t been round to suggest more. Cade could stay drunk, of course. There was alcohol aplenty in the barrels of Auntie Brishen’s whiskey and casks of very good locally brewed ale. But with thorn, the pig would not have disappointed him by staying a pig, and he didn’t feel like dealing with reality just now. Especially not if reality included listening to another chide from Mieka’s wife about polishing up her husband’s accent. Sweet and delicate as the renewed entreaty was, Cade heard the impatience behind it. He bent his head over his plate of no-longer-flaming pork and wished somebody would come by with a full bottle just for him.

“Dearling, you have such a beautiful voice, and you’re so brilliant in the way you think, but there are some people who won’t hear anything you say, because of the way you say it.”

“Anybody worth the talkin’ to won’t be carin’ much, now, will they?”

Fundamentally, she was right. The drunker Mieka got, the fewer g’s attached to the ends of words and the worse his grammar became. Hadn’t Cade worked to smooth out his own accent after it turned sloppy during his years at Sagemaster Emmot’s Academy? He saw the adoption of slurrings and slang as a deliberate, if unrealized at the time, taunt to his mother: typical adolescent rebellion. He also understood why he had abandoned those slumping consonants and harsh vowels. Words were important to him. Vital, in fact. Slapdash speech could not but influence the way he used words on paper. Precise; controlled; things Mieka was only onstage (it never looked that way, but he was). Offstage, he was… Mieka. No sense trying to change him, to make him other than what he was. If that was his wife’s goal, she was doomed to frustration.

“But, Mieka, when there are noble ladies present—”

Among the friends, relations, business associates, and new neighbors in the town of Hilldrop gathered in the little courtyard this night, there was only one noble lady: Cade’s mother. The fact that she was here at all was another shard of reality he didn’t much care for. Yet Lady Jaspiela seemed content to occupy a chair padded with velvet cushions over there under the rose trellis by the kitchen door, where she could survey the company and yet preserve a suitable aristocratic distance. And keep an eye on Derien, Cade added to himself: Derien, his adored little brother whose idea all this had been. One huge party to combine Cayden’s twenty-first Namingday, the Windthistles’ much delayed home-cozying, Touchstone’s recent triumph with “Treasure,” the completion of renovating the barn, and the arrival of Yazz and his new wife, Robel.

Oh, and a belated Namingday party for Mieka’s daughter, whom Cade had glimpsed exactly once since her birth.

“If you’d just be a little more heeding—you meet so many important people now, like Her Ladyship, and what if we’re invited to—”

“Be puttin’ an end to it, lovie,” Mieka laughed. “There’s me girl!”

Somehow young Mistress Windthistle had missed the fact that Lady Jaspiela had been Mieka’s devoted admirer since first they met. The girl didn’t seem to be the shiniest withie in the glass baskets. But there was something else that escaped her, something more… profound wasn’t the word he wanted, but he was drunk and it would have to do. There were distinctions of bloodline and social class to which certain members of the nobility clung like drifting spars after a shipwreck. Manner of dress and address, the precise depth of a bow and the particular flourish of a feathered hat… Mieka had long since sussed out Lady Jaspiela’s rather mundane snobberies. Of course, he knew that Cayden, too, was a snob, and had teased him about it more than once. Cade’s haughtiness was of the intellect, and he had scant patience with what he saw as inferior minds. Mieka claimed to be unable to decide which was worse: the innate arrogance of the aristocrat or the learned conceit of the academic.

I am what I was born, Cade told himself, and he’d much rather be born with a mind than with a mindless zeal for his own antecedents. He blessed the Lord and Lady and all the Angels and Old Gods who had given him the capacity to express himself in words, to step back from whatever was going on around him in order to observe and catalog it for possible future use, to keep himself separated from the seethe of events and emotions that he nonetheless gathered up to feed his art. Rather Vampirish, but that was how things were.

If he was what he was—so, too, was Mieka. And again Cayden wondered why he didn’t find it extraordinary that he hadn’t murdered the Elf for having revealed his secret. He’d even experienced an Elsewhen about it, a few days after their triumph at the Royal wedding celebrations this spring. He took it out now and examined it, allowing himself leisurely enjoyment of Mistress Caitiffer’s shock. And her hatred.

{ “Make no mistake, woman. I will finish you. I know a few things that I’m sure you’d prefer remained unknown in certain quarters.”

“You know nothing!”

“Don’t I?” He smiled. “You’re forgetting what I am, what I can see.”

The old woman’s lips tightened but then she gave a little shrug. “And to ruin me, you’ll offer what you know to the Archduke—”

“Good Gods! Are you truly that stupid? I don’t have to offer him anything. What’s going to happen… well, I’ve already seen it, you know,” he said, lowering his voice as if confessing. “Just as I saw you write the letter to the Archduke that told him what I am. ‘Something to His Grace’s advantage,’ that’s how you phrased it. Purple wax to seal it. I saw it all.”

“And couldn’t prevent it!” she spat. “No more than you could prevent that stupid little Elf from spilling the whole tale one night, or prevent my daughter from telling me after! He was that furious with you, and that drunk, and will be again, and what won’t you be able to stop him doing the next time?” Then, as if the question had been feeding on her insides, she demanded, “Why didn’t you kill him? You knew what he’d done, that he’d betrayed you. You saw it all, and yet you forgave him. Why didn’t you kill him?”

He laughed at her. “Kill the best glisker in the Kingdom? Oh, I don’t think so. He does have his uses. And I’m not quite finished with him yet.” }

Forgive—there was another interesting word. Some part of him knew that Mieka was Mieka, and would do what he would do; as well blame him for breathing. Why fight it? What Cade would fight for, would spend himself to the marrow of his bones fighting for, was that future where Mieka surprised him with a party on his forty-fifth Namingday. He liked taking this Elsewhen out to examine, to see again the grin on Mieka’s face and the little diamond sparkling from the tip of one ear. Especially did he like the singing certainty that Touchstone would still be together, would still be wildly successful— and that Mieka would still be alive.

{ “You didn’t remember, did you?” Mieka challenged.

“Remember? What’s all this, then? Remember what?”

Excited as a child, he gave a little bounce of delight that his surprise had turned out a surprise after all. “Happy Namingday, Cayden!”

He was right; it was past midnight, and it was his Namingday. “Forty-five!” Cade groaned. “Holy Gods, Mieka, I’m too old to still be playin’ a show five nights out of every nine!”

“Oh, I know that,” Mieka said with his most impudent grin. “But try telling it to the two thousand people out there tonight who kept screaming for more!” }

That was the Mieka he wanted to see. Which of Cade’s own decisions led to that Elsewhen, he couldn’t know. Not yet. Maybe not ever. He had to trust in himself, and in Mieka, to make the right choices. But that was the future he wanted, the one he would fight for.

As of tonight, he had exactly twenty-four years to wait.

Ah, but mayhap it hadn’t been an Elsewhen at all, only something concocted by thorn. If that one wasn’t really a possible future, then the other one, the terrifying one, couldn’t be real, either.

{ He stared at the words so hastily scrawled by Kearney Fairwalk, read them once, and again.

Mieka died a few minutes after midnight.

The horror was cold and raw and completely sobering. Into the huge silence his own voice said, “But I’m still here.” }

The magnificent self-importance of it, the colossal arrogance: he, Cayden Silversun, was the only person who truly mattered.

Both visions had come to him while deep in thorn-induced dreams. They weren’t the regular sort of Elsewhen. He couldn’t decide if they had been prompted or merely enhanced by thorn. But he knew that he must accept both, or reject both. Each must be real and possible, or neither must be. He couldn’t pick the one he wanted to believe and choose to ignore the other.

Someone had gone round to light torches throughout the little courtyard, and someone else had come by to refill Cade’s glass when he wasn’t looking. A nice courtyard, it was, and a tidy house, and the newly refurbished barn was as he remembered it from the Elsewhen that had come to him on the day Mieka bought the place. Well, as it had been— would be—before Mieka blew it up with cannon powder.

Cade drank a private toast to the absolute certainty that this vision was truly an Elsewhen, unprompted by thorn, and he wouldn’t have to wait twenty-four years for it. Until it happened, he’d enjoy the prettiness of the thatched-roof cottage and its courtyard and barn, all lit up and filled with food, drink, a bonfire, garlands of beribboned flowers, laughter, music, every charming thing that celebrated a young man’s coming of age.

But no gifts. Not yet, anyway. As the day had progressed into evening—lurching or flowing, depending on whether he was just drinking or whether he and Mieka had sneaked off for another sampling of thorn—he’d begun to wonder if the party itself wasn’t his gift. No, there was always something special to commemorate a man’s twentyfirst. In that future-to-be, when he’d turn forty-five, Mieka had given him a pair of crystal wineglasses. One day he’d have to open that Elsewhen inside his head just to take a closer look at them. Blye’s work, they must have been. And Blye on the sly (ah, there he was, rhyming again!), because without an official hallmark bestowed by the Glasscrafters Guild, she wasn’t allowed to make anything hollow. On the other hand, in twenty-four years, things might have changed. He liked that thought, and tucked it away for further contemplation at a time when he wasn’t owl-eyed.

One day he’d make the choice that led to that future of the wineglasses and the diamond earring. It was all his to decide. He wouldn’t have foreseen it, otherwise, because every Elsewhen he experienced was a direct result of his own actions. The futures that he could not affect, those were the ones he never saw in advance.

The visions had changed over the years—not just their content, but the manner of their occurrence. It used to be that he’d hear a few words, glimpse a scene. As he’d got older, some of the Elsewhens became longer, more elaborate, with greater detail. The turn he’d reviewed just a little while ago, for instance: at fifteen or sixteen, there would have been just the woman and her nasty laughter. Sagemaster Emmot had told him that as the years passed and his brain matured, the visions would mature as well.

“When first this began, your mind didn’t quite know what to do with it. As age and experience increase, your mind will recognize that it needs to respond in certain ways. The first time someone who will become a musician hears music, his brain hasn’t yet learned how to organize the sounds, much less reproduce them. Eventually there is enough music stored in his mind that the response becomes intuitive—but it also requires the application of learned knowledge in order to manage the sounds, arrange them into comprehensible patterns. By the twenty-third year, or thereabouts, the brain has matured through a combination of instinct, experience, and education. When the visions come, you’ll know precisely what they are, how to view them, how to understand them. It may even be that you will be able to control the timing of these visions.”

Gods, how he hoped so. He’d almost stopped being afraid that a turn would take him when he was someplace dangerous—on the stairs, on horseback—because there seemed to be a portion of his brain that took care of his body in the here and now while the Elsewhens were sending his thoughts into the someplace and whenever. Again, the example was the way the vision of Mistress Caitiffer had first taken him: during the time it took to unfold inside his mind, he’d walked from the back door of his parents’ house almost to Blye’s glassworks on Criddow Close. He supposed it was a bit like Mieka’s ability to comport himself with near-perfect normalcy even though the look in those eyes proclaimed that he was thorned to the tips of his delicately pointed ears.

To be sure, in the scant weeks since Touchstone’s first performance of “Treasure,” there had been more Elsewhens than just the one featuring Mieka’s mother-in-law. But that one had been the most satisfying. He’d smiled as he made his threat, and although he wasn’t sure what knowledge he had of her—or would have—that frightened her into compliance, that smile had felt very good. One of the frustrating things about an Elsewhen was that when they occurred he rarely knew what he would know in the future. During the one about his forty-fifth Namingday, for instance, there hadn’t been a thought in his head about why he and Mieka shared a house. He knew that portions of it were his, and portions of it were Mieka’s, but how this had come about was a mystery. Cade had gone over that one several times, trying to glean a hint or two, but he no more understood the reasons for their living arrangement than he knew what Mieka’s upstairs “studio” was for. He knew it existed, because the word had been in his mind, but—would Mieka take up painting? Sculpting? Music? Studio implied art, but if the Elf had any talent other than glisking, Cade had never seen any sign of it. An odd little mystery, and one he looked forward to solving.

The various thorn he’d indulged in during the afternoon had all faded by now. The feasting was over, the dancing had begun, and Cade laughed quietly into his glass as his little brother, Derien, partnered two girls at a time: Cilka and Petrinka Windthistle. He was almost nine, the twins were almost fourteen, and he was already taller than they, already growing the long bones that were his Wizardly heritage. Just as there was the promise of a tall and elegant body in him, there was also the promise of a handsome face, with a singular sweetness about his clear brown eyes. He bowed and flourished in all the right places, and stepped lively around the two laughing white-blond Elfen girls in the movements of the dance, but didn’t dare what their elder brother Jedris did. Cade nearly spluttered his drink as Jed tossed his wife in the air and caught her in strong arms, holding her high off the ground. Blye shrieked and pretended to box his ears. This party was for her, as well; five days ago she, too, had turned twenty-one. She and Jed had celebrated quietly in their home above the glassworks on Criddow Close, enjoying a scrumptious feast sent by Touchstone. Blye was growing truly pretty, Cade decided with a fond smile. Marriage agreed with her. She looked so happy, swinging high in her adoring husband’s arms.

But then she was yelling in earnest, in astonishment, and pointed to the main road.

That was how Cayden discovered his Namingday present.

Not strictly just his, of course. It was for all four of them, for Touchstone.

The wagon came rumbling down the lane, pulled by two huge duncolored horses, driven by Yazz with Robel at his side. It was a beauty. (And so, he noted, was Robel: masses of flaming red hair piled atop her head to make her even taller, a face as sternly perfect as the faces of archaic queens on well-worn coins, and a body made of just the right proportions of sturdy bones, supple muscles, and firmly rounded flesh. Scant wonder Yazz had trudged multiple times through heavy snows to win her.)

All excitement centered on the massive white wagon as it looped round the bonfire and pulled to a stop in the cobbled courtyard. Kearney Fairwalk had promised the absolute latest by way of springs and wheels and lanterns and interior comforts, and Cade supposed that all those things and more were present in abundance, but what made his heart swell to bursting was the way it had been painted. Although the bold red TOUCHSTONE on either side, down below the windows, was good advertising and a point of pride, and the symbols in black below each window made him smile (a spider, a drawn bow, a thistle, and a hawk), it was the painting between the two windows that made his jaw clench and his fists tighten. He knew who had worked it. A map of the Kingdom of Albeyn: green land, brown delineating the main highways, blue for the lakes and rivers and surrounding Ocean Sea, purple jags for the Pennynine Mountains, tiny red dots for all the stops on the Circuits, and gold for Gallantrybanks. Way down at the bottom corner was a little silver hawk with arching wings. The maker’s mark.

“Do you like it? Do you?”

He looked down at his little brother’s flushed, eager face. “It’s—yes.” He swallowed hard, and bit his lip, and smiled. “Yes, I like it.”

All at once the back door opened, stairs unfolded, and Lord Fairwalk stepped cautiously down. After him, less decorous—or perhaps thirstier—leaped Vered Goldbraider and Chattim Czillag. Cade had wondered sporadically through the afternoon whether any of the Shadowshapers would accept the invitation, eventually deciding that they felt it was too much of a drive from Gallantrybanks. Well, evidently not, when Auntie Brishen’s whiskey was on offer.

Cade greeted his friends, accepted their good wishes and the apologies relayed from Rauel Kevelock and Sakary Grainer, saw them provided with brimming cups of whiskey, and prepared to hear all about the marvels of the wagon. He was a trifle miffed that Touchstone wouldn’t be the first to ride in it.

“Well? Waiting for an invite, are you?” Vered demanded. “Go in, have a look!”

Mieka and Jeschenar had already swarmed past and were laughing their delight. Rafcadion ambled over to make a slow, contemplative tour around the wagon while Yazz unhitched the horses. Cade could only stand there, his drink in his hand, still staring at the map.

He knew, in the abstract, that he’d been to all those places and more besides. There was the strange old mansion outside New Halt, for instance, where they’d twice played to an audience of one, and been spectacularly well paid for it. Neither was Lord Rolon Piercehand’s residence, Castle Eyot, picked out on the map, the place where each group on the Royal, Ducal, and Winterly had a few days of rest between the northern and southern portions of the Circuits. It occurred to him that from now on they’d know exactly where they were at all times. What was it Mieka had said once? Something about not always being sure he knew where he was or where he was going, but nice to know where he’d been. With this map, they’d always know the place they’d just been, the place they were at, and the place they soon would be. He wasn’t entirely sure how he felt about that, and couldn’t have explained why. Mayhap it was because one could never tell what might happen in between.

“I agree,” Chat’s voice said at his side, and for a moment he wondered if he’d spoken aloud. The Shadowshapers’ glisker went on, “Better to have a look inside after everyone else has poked through it. A marvel and a wonder it is, no doubt. But me, I’d like a peek at the baby.”

Cade glanced round for someone to act as escort, and decided he himself would do. The crowd thinned considerably ten steps from the wagon, and it was almost quiet when they went into the house by the kitchen door. Mistress Mirdley was there, tidying up by means of an Affinity spell. Once the first plate had been cleared by hand into a rubbish bucket, the others were easy. Dirty plates were held up one by one, and what food remained on them slipped smartly off to join meat, veg, and bread already binned. The trick was to focus the spell narrowly enough so that the usable leftovers on the table and counters didn’t whisk themselves into the bucket as well.

Chat greeted the Trollwife with a bow and a smile, reported that his wife and family were all well, and begged to be allowed a glimpse of the newest Windthistle. Mistress Mirdley gestured towards the hearth, where a large and ornately painted cradle stood just far enough back to provide the baby with warmth but not heat. Leaving the last few plates on the sink counter, she shuffled over to the cradle and twitched back the coverlet.

Jindra had her father’s hands, with the ring and smallest fingers almost the same length, his elegant Elfen ears—and his thick black eyebrows, poor little thing, Cade thought, peering into the cradle. She had been born at Wintering. After Touchstone’s return from the Winterly Circuit, he’d done the polite thing by calling at Wistly Hall with a squashy stuffed toy for the baby and flowers for her mother, but both had been sleeping, so the irises had gone into a vase and the pink bunny had gone into a basket full of other presents. Cade had had a brief glimpse of Jindra’s face: closed long-lashed eyelids, a wisp of black hair straying from beneath a knitted cap—then went into the parlor for a drink, and then departed. In the intervening weeks, there had been rehearsals and performances, and once Mieka had reclaimed his house and moved his family, there’d been no convenient opportunity to come out to Hilldrop for a visit. Nice, reasonable excuses for what Cade admitted to no one but himself: that he avoided Mieka’s wife with the devotion of a Nominative Brother to study of The Consecreations.

“Lovely!” said Chat. “A real heartbreaker!”

There was very little of her mother to be seen in Jindra’s face. The nose, perhaps, and the fullness of the pursed lips, but that was all. Any doubts anyone might have had—well, that Cayden had, and never spoke about—regarding the child’s paternity were obviously ludicrous. Jindra was Mieka’s daughter right enough. She even had those eyes, Cade thought helplessly, as for the very first time in his presence the baby opened her eyes and looked directly at him. Big, bright, changeable eyes, blue-green-brown-gray all at once—but surely it was only imagination that made him see the same sparkle of mischief, the same golden glint of laughter.

What happened then was a thing he had heard about from besotted fathers and read about in sappy poems and seen enacted in sentimental plays. Nonsense, he’d always reckoned it, to think that there could be any sort of fundamental contact between a full-grown adult and a months-old baby.

He’d reckoned wrongly.

Mistress Mirdley stood beside him, nudged him with a shoulder. “You can touch her, you know. She won’t break.”

He saw his own hand reach towards Jindra’s, saw her fist close around one of his fingers. She was still staring up at him. She cooed.

He’d seen her eyes before, of course. He’d seen her, snarling at her own daughter. He didn’t want to remember it, but remember it he did.

{ “Your grandsir was a selfish, spoiled, heartless bastard who cared about drinking, fucking, and thorn. He never gave a damn about your grandmother nor me. He did whatever he pleased with whomever it pleased him to do it with, without a thought to anyone else—” }

Jindra grasped his finger and blinked her extravagant lashes at him. Mistress Mirdley said, “Prettiest little thing, isn’t she? Scant wonder, her parents being such beauties.”

{ The little girl watched with solemn eyes as her father staggered into the house, clutching a huge stuffed toy under one arm. He caught sight of her, laughed, tossed the brown velvet puppy at her. “F’r you, sweetest sweeting!” She made no move towards it, mistrusting of his uncertain limbs. His grin became a scowl. “Well, then? G’on! It’s yours, you silly girl!” When she stayed where she was, warily silent, he kicked the toy into a corner on his way to the bottles on the sideboard and muttered, “A bitch for a bitch—just like y’r mum!” }

The turn didn’t surprise him, exactly. But something else followed instantly; something happened to him that was really very simple. He would do anything to keep this baby from becoming that mute, mistrustful little girl, that damaged woman. He would fight for her. Protect her. Keep her safe.

Jindra latched on to his thumb with her other fist. She smiled at him, all toothless pink gums and rosebud mouth, plump cheeks and beguiling eyes. He tried to tell himself that everybody went all gooey about babies. Hardened criminals became mush at the sight of helpless infants. Babies were tiny and fragile and defenseless and vulnerable and—and good Gods, she wasn’t even his.

{ “Cade! They accepted me, I’m in!”

“Of course you are.” He set aside his book and looked over the rims of his spectacles, smiling at the whirlwind of long black hair and colorful fringed shawls that danced through the drawing room. “Your father and I always said you’d be accepted, didn’t we?”

“Oh, but Fa is forever telling me I can do anything—”

“—and do it perfectly the first time you try it, yes, I know.” He pretended a dramatic sigh. “The regrettable incident with the carriage proves he’s not completely objective about these things. But when are you going to learn that I am always right?” }

And he would have to be, wouldn’t he? As the second turn vanished and he again felt Jindra’s hands clinging to him, he realized he would have to make the right decision every single time.

The reminder was like a last lingering tweak of thorn in his veins: she wasn’t even his. And, like thorn, it mocked reality.

But he knew the difference between what he dreamed and what was real. Jindra was real. All else was might-be or could-be or must-never-be.

She was one more thing to fight for, was Jindra Windthistle.

Thornlost © Melanie Rawn, 2014

All right, I’ll admit it.

I’m hooked. I had a mixed reaction to Elsewhens but I very much want this book! And I’m so glad it’s out soon.